DIT, Aungier Street, played host to the annual indie games festival, State of Play 2015 on Wednesday 20th May. (Watch back at www.twitch.tv).

During the afternoon students and indies demoed their projects and for the first time there was an academic session for showing research. However we the authors, were really only at the evening talks so we will have to get feedback from others on the afternoon sessions. The images from Bryan Duggan of DIT show a good crowd though.

When we arrived at 6pm the room at the top of Aungier Street was almost full with at least one hundred people. A mix of students, lecturers and industry representatives from the cream of #IrishGameDev were in attendance. bitSmith, Simteractive, SixMinute, Fungus games, and a number of other indie games developers joined an enthusiastic crowd. Seats were at a premium as latecomers streamed in filling up the space, helping give a great atmosphere before the talks even began.

Hugh McAtamney, Head of School of Media in DIT introducing the event, the fifth state of play. He thanked everyone who participated in the games demos earlier in the day. After a brief talk about some of the mechanics of games, in the context of his own children, Elaine Reynolds of Simteractive took to the stage.

Elaine’s talk looked at the day to day aspects of running a games company, looking at everything from running a games company, to the basic office management stuff such as ordering bin tags. As a person running a company, she talk about the importance of prioritising tasks, while also juggling all the day to day components of running a live team. She spoke about tensions that can cause problems in a game, such as the balance between improving a game versus shipping a game, or quality versus quantity, or learning to say no. She mentioned the opportunity cost of doing everything, time effort and money.

The decisions theme continued, looking at all of the different decisions needed in game design; in her case making a game where you run a holiday resort. Elaine then showed off some screenshots of her new game, and asked the crowd for playtesters, who can sign up at simteractive.com

Next up was Colm Larkin of Gambrinous, who are making the game Guild of Dungeoneering. He said that he had announced his game “embarassingly early”, but then went on to talk about the positive side effects, such as getting feedback early from critics, players, peers. He mentioned sharing early also helped build a portfolio, take on board feedback, and make deep changes to the game. It allows you to rapidly prototype lots of concepts before trying to focus on a  bigger project. He then went onto places you can talk online, starting with a blog on Tumblr and posting articles on Gamasutra.

bigger project. He then went onto places you can talk online, starting with a blog on Tumblr and posting articles on Gamasutra.

He also mentioned sharing in person, standing there, watching people play the game, take feedback and make a better game because of it. He highlighted events like State of Play and gamejams. At gamejams he noted the shared deadline was a great way to force you to deliver and share your work. He wrapped up “saying create, but also share.” (Editor: of course it has been a great year for Guild of Dungeoneering given that it was nominated for Casual Connect Indie this year in Amsterdam and won most promising game in development. See also recent article in Irish Times).

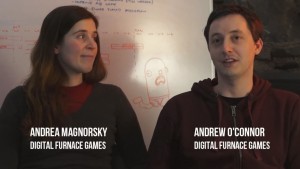

Rapidly following him was Chris Gregan of Fungus Games. Having previously worked at Playfirst and Instinct Technology, he talked about putting in lots of unpaid time into IP that the company owns, and the day you leave them company (even if you are a founder), you lose all the access to it. “After twelve years of sweat, I had zero access to the hundreds of thousands of lines of code I wrote”. He mentioned two proprietary game engines he worked on, which have gone obsolete and disappeared. Based on this, he has moved towards open source. Fungus, is an open source engine for making story driven games.

Fungus took inspiration from twine and redpipe, and the communities around them. Fungus hopes to attract lots of users, remain open sou rce and sell training programs. An open source business model is not easy, or a path to riches, but a way for a developer to eliminate barriers to adoption. You don’t need to open source everything, maybe certain scripts and other parts of the game, while keeping the rest proprietary.

rce and sell training programs. An open source business model is not easy, or a path to riches, but a way for a developer to eliminate barriers to adoption. You don’t need to open source everything, maybe certain scripts and other parts of the game, while keeping the rest proprietary.

When it came to education, he advised attendees to keep things open source, using something like github. This is especially important with group projects which means future employers can see how a team works together and who has committed code. He also mentioned that a license, such as the Creative Commons, should be added. If it’s not there, others can’t use it as you have the copyright. He mentioned the overwhelming support he’s received from the local Irish industry including help with code, workshops, documentation, promotion, and advice. (Editor: See recent article on Fungus in the Irish Times)

Chris Gregan

Next up was Andrew Deegan of Sugra Games. Andrew has seven years of experience, across a range of projects in toys, games, free to play, starting up two companies, raising €350,000 in funding and winning several awards. He noted that there are only about 200 paid development roles in Ireland, with many companies not making much money, and many in it for the passion. When he is hiring he is more interested in specialists, rather than generalists. For him a key question people should ask themselves is do I want to be an entrepreneur or an employee? He has worked in four games companies, two as an employee and two as an entrepreneur. Having been both, what has he learned?

When you work for yourself, you have a huge amount of responsibility and multiple roles. When you are an employee you have a specific role. When it comes to work hours, people do lots of hours in all companies, but more so in your own companies. In terms of acclaim and critical reception?. In Breakout, he got lots of critical acclaim, working with lots of companies such as Acclaim and Hasbro. In Jolt, there wasn’t much acclaim, the market didn’t like the game, the media didn’t like it. In Megazebra, they had over 8 million people play the game, with continued demand with people looking for new content. With Sugra, he said that they haven’t made a hit (yet!), making two versions of one game, and then publishing games from Japan, but not having hit critical acclaim.

He then looked at his income. In his first job despite getting support from DIT, patents and Enterprise Ireland, he made little to no money. Then he talked about working for another company, having low responsibility, but making more money. When it came to his second company, as an entrepreneur, he had to give himself a paycut to keep things going. If you’re going to be an entrepreneur, you need to be prepared to earn nothing.

Finally he talked about stress. There was more stress as an entrepreneur, having to build the product, attend events and get on with things. Working for people, there was less stress with more money. Back into stress as an entrepreneur, which shoots up when you get investment, take on a team, and run the company, or chase sales. He then talked about love for the project, with the first year being fun and new, and over time, interest was lost in both types of companies. So overall things were happier working for a company, with less stress, more money and more fun. However in both types of companies the fun tapers off.

Next up was Louise McKeown who spoke about the potential of Radical Heterogenous Game Spaces. For her there were a lack of characters in her gaming history that she could identify with. She tried to look back at times in her teens when she played a game, and connected to a strong female character, but couldn’t find one. While she enjoyed characters in games such as Final Fantasy 7, she couldn’t relate to them, she would never be like them, or look like them, or be the protagonist in the game.

A recurring theme was that stories very rarely go outside of the heteronormative masculine norm. She talked about Super Metroid, and her experience playing the game, knowing she was female, and how that helped her feel empowered. She spoke about Gone Home by Fullbright company, as a space where female characters felt comfortable, even though in that game it portrays a world where women love and respect each other, all within the house and no external masculine influence to make the environment hostile.

bitSmith Games’s Owen Harris, a veteran of state of play and lecturer on the BA in Game Design in DIT then took the stage. His talk was about the journey of finding his voice as a game designer. He talked about messing with game engines and technologies for a decade, and that four years ago he dedicated himself to being a game designer, which he thought were all mysterious wizards with archaic knowledge, formulas and information. He found it very intimidating, looking at how different games were there, and tried to emulate it himself. He tried to think, speak and make games the way he thought others did, from a disciplined, analytic space. He wasn’t happy, ending up lost, unhappy and thinking it would never happen.

Then he went to a fantasy writing convention and listened to a Neil Gaimen talk. Neil spoke about his early career as a writer, balancing the tension between what you want to do, and what you need to do to get by, and the importance of finding your own voice.

Owen found this inspirational and this informed an experience he is designing called Deep, which is a project controlled by breathing. The project is very difficult, needing a VR headset which isn’t out, and a controller he’s only made one of, which can only be played at events.

Despite this, it’s gotten a lot of positive critical reception, including lots of emails from people asking him for emotional help.

If you feel scared and intimidated by the towering titans of game design masters, perhaps all you need to is step out of their shadows. You don’t need to be a mighty wizard, instead looking at the fool for inspiration. Drop the desire to be smart and successful, and instead approach game design in a way that’s fun, silly and weird.

After an interval, Mitu Khandaker-Kokoris took the stage, an independent game developer (at the one woman The Tiniest Shark) and videogames PhD researcher (at University of Portsmouth, UK).  Her talk focused on play, caring about people, and the player.

Her talk focused on play, caring about people, and the player.

She recounted how she had loved games since the commodore 64 and the Amstrad PCW. She discovered a game called Jinxter, a British text based adventure game. It taught her about comedy in games. Other influences were more from TV and film.

When she was 13/14, she saw an X Files episode about a super intelligent virus let loose on the internet. A key figure in the episode was Invisigoth, a female hacker, and entertainment software developer. This was the first time she realised that you could work at making games. That was the moment that set her on the path of game developement as a career option.

She also had an interest in space, having been brought to a planetarium in London, and realised the scale of the universe, and how tiny earth was. This affected her thinking when it came to making video games, being tiny but connected to other things. Her game design has reflected this, looking at how things are connected, and how people interact, or self reflect. Games can be represented in many ways, from abstract to comedic.

She looked at games from the context of art through play. Play puts us at odds with ourself, at least interesting play does. As we play, we confront different realities, which is similar to plays, painting and other types of media. Games or other artfowms are a perfect vehicle for exploring the world around you.

Her talk then moved onto diversity, and how women are represented in games, and the vocabulary that has emerged. She discussed diversity, inherent (gender, race, sexuality etc) vs acquired (life experiences, habits that set you apart, communities you’ve engaged with, places you’ve been). She discussed Miyomoto’s work, and how this has been about recapturing childhood experiences, and putting them into his game design.

Next up was Zuraida Buter from the Netherlands, executive director of Global Game Jam (GJJ) and curator of numerous play festivals. With no laptop we were treated to audience participation. She had five wooden shoes, and brought several members of the crowd to the front to play Turtle Wushu. Last person standing wins (Vicky Lee did in the end).

After that, she began talking about GJJ. In 2009, there were 53 locations worldwide which ran gamejams, compared to today where Brazil has over 70 venues. This year, over 25,000 people across over 70 countries participated in game jams and collaborating and making new things in digital and board games. Year on year, numbers are increading, and used the example of Egypt where over 2,000 people are participating, in countries where they don’t have a legacy of making games, and even where there is conflict ongoing in the countries.

She then spoke about the Dutch Game Garden, a business centre/incubator in Utrecht for games. Starting with a team of three people, and supported by local government who saw some economic benefit and backed it. Six or seven companies started, and it began growing and growing. They started aiming to support students who wanted to set up a studio after graduation, but in 2010 they moved to a bigger building, with five floors with nearly fifty games companies, some established, others starting off from scratch.

People went to shows like GDC, Tokyo Game Show, and met each other and networked. It allowed people from the same country to meet, who hadn’t met in the Netherlands. They started to run different events to let people to network with other developers, and showcase their talent. On the back of this, they set up Indigo, which has 36 teams showcasing their games, letting students mix with professionals, and offering a gallery which is open to the public. Year on year, the numbers participating are rising, and year on year the quality is rising.

Calling herself a playful culture advisor, she talked about the interaction between participation, creativity, performance, encounters, curiosity and spectatorship. In this, she’s attended a lot of different festivals and groups, such as the Copenhagen Game Collective, Nordic Games Indie nights, and talked about play culture in the context of real-life events, getting people to interact and have fun together, reworking old classic games, or just making fun games up on the spot. She also mentioned Amaze in Berlin, Inis Spraoi in Ireland and the Playful Arts Festival. You can see more about these events at the Playful Culture tumblr.

Next up was RICHARD LEMARCHMAND, lecturer at the Interactive Media & Games Division of the School of Cinematic Arts at the University of Southern California, and former Lead and Co-Lead Game Designer of the award-winning Uncharted series for the Sony PlayStation 3 at Naughty Dog studio. Previous to that, he worked in Crystal Dynamix where he worked on Gex, Soul Reaver and Pandemonian.

His first start was MicroProse where he helped start up their console game division. He counts himself lucky for becoming a game designer, and got a lot of help from mentors along the way. He loves the thrill of making a game, and then seeing someone play it. Games have the potential to combine the best of culture, and are a meta art form as you can combine different types of artforms into once place. Games are also interactive systems, which can respond to players when they make inputs.

Overall his talk looked at Systems, Games and Balance. Devising the systems of games is the main goal. We’re at the brink of a revolution of creativity and innovation, which comes to a head in games. Examples such as biometric inputs, new displays, robotics, small affordable CPU’s and touch screens will lead to new types of arts, such as mixed hybrid interactive performances. The tech is a candy shop of tools for scientists and artists. Although without ideas, all the tech counts for nothing, but right now there is a renaissance in game design, with lots of different types of games, from triple A to games like Monument Valley, and all the other indie games. These cater for all sorts of different styles and spaces. He also name checked a lot of new innovative Irish games, such as Guild of Dungeoneering, Curtain, Darkside Detective and Owen’s game, Deep.

For him games are an incredibly ancient form of human culture, possibly pre-dating language and writing. Referring to the work of games sociologist, Roger Caillois, he discussed Caillois’ categorisation of four primary types of games – games of competition, games of chance, games of make believe/ mimicry, and games of vertigo, which temporarily change your perception (roller coasters, spinning in a circle to get dizzy).

Soul Reaver was inspired by painters, books and German expressionist films. Uncharted, tried to referenc e different forms of culture, in an era of blockbuster type games like Indiana Jones, Die Hard, King Solomons mines etc., and now they are working on games that connect with different forms of culture.

e different forms of culture, in an era of blockbuster type games like Indiana Jones, Die Hard, King Solomons mines etc., and now they are working on games that connect with different forms of culture.

On systems, he said they’re all around in the physical world. Made up of interconnected elements, that cause patterns to emerge. Humans often see beauty in the things made my processes (i.e. basalt columns at the Giant’s Causeway, geometrics, or supernovas, snowflake crystals, or images showing fractal patterns in nature. ) Systemic structure are in nature, with fractals and symmetry in flowers, and weird beauty in complex structures like a termite mound, or structural beauty of objects humans build, such as engineering that makes new or old architecture.

With the advent of digital communities, this has changed, with mathemetical models which look like organic structures. Over the course of the 20th century, artists followed sets of rules, that allowed others to create different types of art, or systems of geometry, or 3D structures. By the middle of the 20th century, scholars founded a discipline of cybernetics, now known as systems dynamics. Systems are governed by feedback loops, such as stabilisiing feedback loops, like a thermostat, or a runaway loop, like compound interest. Emergence is where larger entities arise through the result of interactions among smaller or simpler entities, such as ants making a complex anthill.

He moved on to talking about games as systems. Of numbers, logic, relationships of space and time, interactions and vertigo, and feedback loops. Emergence in game design allow events, a holy grail in game design, and seen more in sandbox games, emerge. Games have elements of players, objectives, rules, procedures, resources, conflict, boundaries and outcome, and the interconnections between them. Talking about Last of Us, he talked about Control systems as important, helping bring the players close to their character. Game systems such as health, ammo, gameplay systems controlling NPC’s and enemies in the game. Multi pass rendering brings the environment to life, and light.

He talked about the nemesis system in Shadow of Mordor, which generates the interactions between different Orcs, and they change how they react to you. He then talked about Game Feel by Steve Swink, talking about how controls feel in racing games, or environmental games. He talks about the Game Feel, bringing together players, ideas, beliefs, generalisations, fantasies, memories, and the world around them. This has inputs, response, metaphors, context, polish and rules, which create feedback loop that affect interaction, sound. All give a perceptual field, taken from psychology.

He then talked about balance in games, and how feedback loops work in mechanics, code and the experience points system in games. The more you destroy, get experience, level up. A runaway feedback loop. As you get better, opponents get more difficult, giving a balancing feedback loop. He then showed the telemetrics system in Uncharted, which let them see difficulty spikes from play testers, or to confirm that the game was as challenging as they wanted it to be.

Crunch

In concluding Richard started to talk about work life balance for game developers. If you don’t get the right life balance, games can be very dangerous. Game development crunch is working from morning to night, week on week, with no respite, to finish some crucially important spike. Crunch can do damage to people’s lives, especially in triple A. In the indie community, while there aren’t some of these issues, there is a tendency to put crunch on a pedestal to stay up till dawn day after day. It’s a seductive thing, making you feel cool, creative and brave, or that crunch is okay if you’re doing it on a game you own, on your own term, as opposed to working for someone as an employee.

He said there were many artists living on the breadline, struggling to pay rent and feed themselves. It may be romantic, but it’s a failure to recognise the seriousness of the situation Crunch can do physical harm by not getting enough exercise, eating right, getting a repetitive stress injury. It can do psychological harm, not keeping in touch with friends, not getting mental downtime. It becomes unsustainable to the point where you can’t do your job. When game devs leave the industry, they take all the hard won knowledge with them out of the industry and those left behind have to reinvent the wheel over and over. Crunch can be addictive, and it can be dangerous to let it become a habit.

His message was that crunch is counter productive. Management studies show after 4-6 weeks of a 60/80 hour week, you’re less productive than someone working a 40 hours week. Looking at how to tackle the problem, you can look at how you make a game. “Making games is hard”. Game developement takes longer than you think, especially when you start. Something that has an hour allocated in the plan, takes a day. There’s lots of stuff that comes along that couldn’t be foreseen, and most of this work is never scheduled, making the project a lot bigger than it is. Projects are often not planned well, or at all, or there’s no overreaching arc, or wing it and hope for the best, but don’t plan for the worst. These can lead to crunch. There is a myth of infinite time, such as the first day of a project, which very quickly runs out. He referenced the Cerny model of game design, which has a set of best practices similar to AGILE, but specifically for games.

Studios like Naughty Dog or Insomniac use the method to have a proper pre-production phase and to explore game design, designing prototypes, and having a simple plan for a well scoped project. There needs to be space at the end to polish, find and fix bugs, and continue improving. You can avoid crunch by working less, but more productively.

He gave some tips. Plan work, stop working when you’re finished. Don’t keep working because you enjoy it, or because you are in the middle of a problem. Passion can cause a problem that leads to crunch, but go to sleep so you have something exciting to get back to, when you’re refreshed after a good night’s sleep. he also looked at your desk situation, making sure that your ergonomics of your workstation are correct for you. Studies show that sitting for a long time, your body and brain do things that are bad for you, so if you can stand up regularly, this can interrupt you so you can move and feel better. Try and control your sleep patterns, i.e. don’t drink caffeine after a certain times, or light emitting screens in the hour before you go to sleep. Try go to bed at the same fixed time. Make sure you’re eating fresh fruit and vegetables, and most important get face to face social time, and try and see them once or twice a week. Once you’re working passionately, you can get socially isolated, and getting real-life contact can help get emotional and mental benefits. Happy developers are as important as happy players. If you’re not happy in your work, it’ll show in your game.

Crunch can happen, but it’s about finding the balance. When you’re working extra hard, make sure it’s sustainable. balanced sustainable methods in business practices in games keep people around. If business cultures are welcoming, more diverse people will join, and this can only benefit the general development community. In other sectors such as writing, film, reading, people work till their 70’s. This doesn’t happen in games, but some day it will.

The evening wrapped up with Hugh thanking all the speakers, and a few words from DIT President Prof. Brian Norton. He was happy for DIT to host State of Play, an education in many ways for him and referred to the diversity and maturity of games. He talked about new DIT campus in development in Grangegorman in Dublin which would help bring games together with other artforms in new facilities, and thanked the crowd.

Afterwards people moved to 4 Dame Lane for some food, drink and tunes.

Notes written by Jamie McCormick. Edited by Aphra Kerr.

If you spot any errors or would like us to rephrase something just get in touch.

Share your pictures on our forums or @gamedev_ie

of a skilled fighter. He’s not necessarily a ninja or elite fighter, but he’s definitely an accomplished hand-to-hand fighter in our game and the Fury Road movie, whereas I don’t know if that was the case in the first three films.”

of a skilled fighter. He’s not necessarily a ninja or elite fighter, but he’s definitely an accomplished hand-to-hand fighter in our game and the Fury Road movie, whereas I don’t know if that was the case in the first three films.” y were working on a Tomb Raider game. Half the accents were Irish. There was definitely grassroots talent.”

y were working on a Tomb Raider game. Half the accents were Irish. There was definitely grassroots talent.”

With new speakers being added all the time there is now an extensive list of speakers for the Sept. 10th event in the Mansion House, Dublin which this year has a focus on product innovation.

With new speakers being added all the time there is now an extensive list of speakers for the Sept. 10th event in the Mansion House, Dublin which this year has a focus on product innovation.

Scopely Deal

Scopely Deal

esparks 1: 04 –

esparks 1: 04 –

ss a range of areas.

ss a range of areas.

rce and sell training programs. An open source business model is not easy, or a path to riches, but a way for a developer to eliminate barriers to adoption. You don’t need to open source everything, maybe certain scripts and other parts of the game, while keeping the rest proprietary.

rce and sell training programs. An open source business model is not easy, or a path to riches, but a way for a developer to eliminate barriers to adoption. You don’t need to open source everything, maybe certain scripts and other parts of the game, while keeping the rest proprietary.

e different forms of culture, in an era of blockbuster type games like Indiana Jones, Die Hard, King Solomons mines etc., and now they are working on games that connect with different forms of culture.

e different forms of culture, in an era of blockbuster type games like Indiana Jones, Die Hard, King Solomons mines etc., and now they are working on games that connect with different forms of culture.